“The Subtlest Maze of All”

Once more, into the labyrinth: When was The Tempest written? Whether you ask this question from an Oxfordian, Stratfordian, Jonsonian or non-aligned Shakespearean perspective, there is only one absolutely certain answer:

Once more, into the labyrinth: When was The Tempest written? Whether you ask this question from an Oxfordian, Stratfordian, Jonsonian or non-aligned Shakespearean perspective, there is only one absolutely certain answer:

The Tempest was written sometime before its first publication in 1623.

Though scholars seldom linger long on this unsatisfactory terminus ante quem, the plain truth is that whatever play King James and his court enjoyed on Nov. 1, 1611, IT MAY NOT HAVE BEEN THE SAME, in all respects, as The Tempest that took pride of place twelve years later in the First Folio. With no prior text for comparison, we can’t rule out the possibility of authorial revision, additions by unattributed “co-authors”, editorial intrusions by Ralph Crane or Ben Jonson, or in-house modifications by the players themselves, however uncomfortable these unknown variables leave us. Therefore, the “rhetoric and logic of academic discourse” (Roger Stritmatter’s phrase) we adopt for examining any aspect of the play contingent upon this elusive date should reflect this basic limitation on our knowledge.

My theory – that Ben Jonson was primarily responsible for The Tempest of 1623 – posits an intentional correspondence between The Alchemist (published 1612) and its near-perfect inversion, The Tempest, (documented as performed twice at court, in 1611 and 1613). With this premise in mind, it is probably no coincidence that Jonson himself provides an earlier terminus ante quem for The Tempest when he embeds the date of the initial performance of Bartholomew Fair within the text of his play. On “the one and thirtieth day of October, 1614″, he tells us, – the day before Hallowmas, that is – he offered the public a rambunctious farce, one in which he seems to cast aspersions on The Tempest that had been performed for the Hallowmas festivities of 1611:

If there be never a servant monster i’ the Fair, who can help it, he says, nor a nest of antics? He is loath to make nature afraid in his plays, like those that beget tales, tempests, and suchlike drolleries, to mix his head with other men’s heels; let the concupiscence of jigs and dances reign as strong as it will amongst you.

If the documents of court performances in 1611 and 1613 had not survived, Jonson’s sly but unmistakable allusions to Caliban and Trinculo under the gabardine would have been the strongest indication available to scholars that The Tempest must have been written before 1614 – except for one pesky detail. This play, too, was not published until much later, in 1631.

If the documents of court performances in 1611 and 1613 had not survived, Jonson’s sly but unmistakable allusions to Caliban and Trinculo under the gabardine would have been the strongest indication available to scholars that The Tempest must have been written before 1614 – except for one pesky detail. This play, too, was not published until much later, in 1631.

Yes, we do have a record of Bartholomew Fair played at court on Hallowmas, the following day, confirming Jonson’s internal date. However, we have no text or manuscript dated 1614 to prove that Jonson’s embedded references to servant monsters and tempests were in the play performed on that day. When we accept this covert allusion as evidence in dating The Tempest, we do so on faith. Jonson’s complete overhaul of Every Man in His Humour for publication in his 1616 Collected Works should keep us alert to the chance that he may have inserted something new into the text, convenient to his own purposes.

On the other hand, if we can be certain that no one has monkeyed with the 1612 publication date for The Alchemist (as Thomas Pavier did with his false dating of Shakespearean quartos in 1619), I believe that this play will eventually yield the surest terminus ante quem, or date before which The Tempest must have been written. David Lucking has already begun the work, with the intriguing correspondences between the two plays that he revealed in 2004 (“Carrying Tempest in his Hand and Voice: The Figure of the Magician in Jonson and Shakespeare“). When his project is carried forward to cover every act in both plays, those who play The Tempest’s Dating Game may begin to shift their focus away from Strachey’s letter and onto Jonson’s securely-dated Alchemist.

Now for the other side of the question: What is the earliest possible date that anyone could have written The Tempest? Here, the terminus post quem theories become infinitely more subjective and nebulous. However, the paper I delivered at the Shakespeare Symposium in Watertown (“Caliban’s Dream and Shakespeare’s Purge”, May 2010) offered strong evidence that the author of The Tempest drew on the play Satiromastix, published in 1602. Solely on the basis of Caliban and Prospero’s debt to Captain Tucca (a character who appears in Jonson’s Poetaster and reappears in Satiromastix), I am certain that The Tempest must have been written after these two plays of 1601, which were furiously rushed into print by 1602.

Richard Malim’s theory that the mysterious Tragedy of the Spanish Maze, played at court on Shrove Monday, (February 11, 1605) was really The Tempest is truly tempting, especially from my point of view. Five months after Edward Oxenford’s lonely death on June 24, 1604 – a death for which not one recorded soul shed a tear or wrote an open, sincere epitaph – the court of King James began its Christmas Revels season with a Hallowmas production of Othello, followed by six additional plays attributed to “Shaxberd”.

Richard Malim’s theory that the mysterious Tragedy of the Spanish Maze, played at court on Shrove Monday, (February 11, 1605) was really The Tempest is truly tempting, especially from my point of view. Five months after Edward Oxenford’s lonely death on June 24, 1604 – a death for which not one recorded soul shed a tear or wrote an open, sincere epitaph – the court of King James began its Christmas Revels season with a Hallowmas production of Othello, followed by six additional plays attributed to “Shaxberd”.

Curiously, the only other playwright included in this Shax-fest was Ben Jonson, whose two famous comedies, first Every Man Out of His Humour and then Every Man In His Humour, served as bridges between performances of Henry V , Love’s Labour’s Lost and The Merchant of Venice. As Malim wisely observes:

Why [Every Man Out of His Humour] was chosen baffles the orthodox professor Peter Thomson, but its clear caricatures of both Shakespeare and Oxford, and the demonstration of the relationship between them, readily explain why the choice was made: to keep the record straight.

Just imagine! A third, new play, written by Benjamin Jonson specifically for this Shrovetide occasion honoring his beloved “Shakespeare”, the master-poet who gave him that humiliating “purge”. Here’s his auspicious chance to have Lean Macilente (who’d just appeared onstage in Every Man Out of His Humour) bid a Lenten farewell to the Lord of Misrule embodied by dark, dishonest Iago and merry Sir John Falstaff – ah, heart be still! I confess, this theory sounds terribly, seductively reasonable to me.

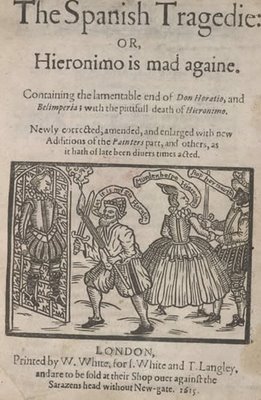

Even the title fits Jonson all too well, making it almost impossible to resist. Poor Ben, the apprentice Bricklayer, had been publicly scorned in Satiromastix for his rugged acting in The Spanish Tragedy. And his Masque of Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue shows what a strong hold the figure of the labyrinth had on his poetic imagination. “The Subtlest Maze of All”, a phrase from this masque, is the subtitle of Robert Wiltenburg’s Ben Jonson and Self-Love (1990). Yes, indeed, there’s solid ore to mine in this vein.

And yet…and yet…alas! I’m afraid I have to agree with R. Chris Hassel, who faced a similar temptation when imagining the possible relevance of the “lost play” A historie of the crueltie of a stepmother (1578) to his excellent thesis:

However interesting these early parallels might seem, they are finally, of course, inconclusive without an actual play.

~Marie Merkel

Very convincing, Marie! Now I’m tempted to read more of Jonson’s plays. Jonson was suspected (by David Roper,I think) of writing the memorial placque “Stay, passenger..” and enciphering the name of Edward De Vere within it. I think Alan Green also found the Triple Tau symbol in that message. Jonson must have been a Freemason who wanted a brother to get credit for his work, though he had to be a bit devious and ambiguous to reach that goal.

Best,

Helen

Thanks, Helen. Jonson’s satiric plays rarely speak to the heart, but I have no doubt that his heart was capable of great, mysterious love. That side of him shows up more in his poems and masques, and in the love returned to him by the “sons of Ben”.

Jonson was probably as honest as he could be – and NOT referring to William of Stratford!! – when he famously declared, “I did love the man, and do honour his memory, this side idolatry”. For Jonson, the correct side of idolatry in terms of Edward Oxenford would have been a side that recognized all the master’s “faults” and “crimes”, both personal and literary. I honor Jonson as a prime mover in making sure that “Shakespeare’s” plays got published, something that no one may ever be able to prove, but I firmly believe to be so.

David Roper’s solution to “Stay, passenger…” (with the three T’s lined up for the Triple Tau you mention) is very intriguing, but unfortunately, we can’t be sure of the exact lettering on the original plaque. Just the difference of one letter will change the reading of a suspected Cardano grille.

If you haven’t read any of Jonson’s plays recently, I recommend starting with his first hit, Every Man In His Humour, making sure to read THE ITALIAN VERSION, so that you’ll have a close acquaintance with Jonson’s Elizabethan versions of “Prospero” and “Stephano” to keep you company the next time you take in The Tempest.

Best wishes,

Marie

Dear Marie,

In determining the no-later-than-this-date of ‘The Tempest’, I ask as a neophyte, does not the epilogue bear unmistakable similarity to Oxford’s writing and religious interests, namely the language and themes of mercy and superior power of prayer? Marked Geneva Bible passages and the theme of mercy in the epilogue are one thread tied to the Merchant of Venice exhortation, “We do pray for mercy.”

That mercy theme goes with another Geneva Bible referenced theme, the divine weapon, prayer. Remember that Oxford declared next to one of the passages in the apocryphal book Wisdom, “The weapon of the godly is prayer.” In the epilogue it says, “Unless I be reliev’d by prayer/ Which pierces so that it assaults/ Mercy itself and frees all faults.”

Thus the epilogue has these two features, traceable to the Geneva Bible marginalia, that are favorable to an argument that Oxford authored this part of ‘The Tempest’. And, to get back to answering our primary question, if he wrote the epilogue, he wrote it before he conked in 1604. Bingo, that part at least written no later than 1604.

Finally, we have a self-referential name, as always hidden in plain sight, the name of the Magus, Prospero. Where does that fit in? In Latin prospero means “to give a favorable issue to”. Our general impression is that Prospero is the magician of art permeating everyone’s feeling and knowing no temporal bounds. For whom does Prospero portend fondly, give favorable issue to? The epilogue’s image is of billowed sails for the pray-er’s life’s work and soul, both embarking into the unknown. Prospero as good fortune releases the pray-er from his bands. The epilogue writer’s last breath beneficently asks forgiveness, indulgences. The spirit ship makes way, full “with gentle breath of yours my sails.” This goes beyond holy dispensation–he needs posterity’s breath to speak his lines or the spirit of Oxford is buried with his name.

The epilogue answers the question who, and the same who died no later than 1604.

Best wishes,

William Ray

Dear William,

Excellent observations, which had me reading all morning yesterday, mostly on the themes of mercy to be found in Ben Jonson’s works, which so often comment on “Shakespeare”.

You wrote:

I agree that Oxford, in his works attributed to “Shakespeare”, often engages with the theme of “mercy”, most memorably in Merchant of Venice, while he uses the word itself most often (16 times) in Measure for Measure. He also makes good conversational use of “mercy” as an interjection, in the common phrase, “I cry you mercy”. One can’t help but wonder what excruciating moment in Oxford’s life under Elizabeth called forth his eloquent “quality of mercy” speech.

On “the superior power of prayer”, as one of Oxford’s religious interests, I’m guessing that you’re referring to the Geneva Bible annotation, “the weapon of the godly is prayer”, right? I’ve never assessed the plays themselves for evidence on the author’s opinions about the efficacy of prayer, compared to the opinions of his rival playwrights, such as Jonson, whom I think wrote the epilogue. “Weapon” does suggest something slightly sinister, which gives this sentence an ambiguous cast. If we knew the author disliked bible-thumping hypocrites, we’d might put a different spin on it than we would if we knew he was terrified of Satan, and turned to prayer to defeat the forces of sin and temptation within him.

Even if I was sure that Oxford was, indeed, the author of those words written in his Geneva Bible (the handwriting doesn’t look much like his to me), I don’t think this, on its own, would be strong evidence of his authorship of the epilogue. First, we’d need to show that Oxford’s attitude towards prayer and mercy was unique, and readily distinguishable from his fellows.

On the meaning of “Prospero”, your Latin definition of “to give a favorable issue to”, (which seems tailor-made for “auspicious”), comes very close in meaning to the one I found for Prospero: “to render fortunate”. At the top of my google search results was our colleague Michael Delahoyde, quoting Harold Bloom on the meaning of Prospero’s name:

That passage is circled with exclamation points in my copy of Bloom. “Prospero”, of course, first showed up on the Elizabethan stage (along with “Stephano”) in Ben Jonson’s Every Man in His Humor, one of the two Jonson plays staged during the 1604/5 “Shax-fest”. As the Vaughans emphasize in their edition of the play, “Prospero is the right (legitimate) Duke of Milan“.

In Hebrew, Jonson’s full name, “Benjamin”, means “son of the right” or “son of fortune”. Jonson gave issue to a whole tribe of hopeful poets, that proudly called themselves, “Sons of Ben”. So then, if Prospero is “the fortunate one”, and Benjamin is “the son of fortune”, where does this lead us? In my view, the character of Prospero in The Tempest was designed to evoke four distinct individuals: King James, John Dee, Edward de Vere and his rebellious poetic son, Benjamin Jonson.

You wrote:

Great question. First, I hadn’t thought of that aspect of him, as having “no temporal bounds”. Could it be that he’s already a ghost? Very appropriate for Hallowmas, I’d say! “Permeating everyone’s feeling” – yes, he does that, doesn’t he? But so much so that Prospero reminds some readers of an irritable old stage manager. No one does anything – smile, frown, kiss or break wind – without his say-so. To me, that is so un-Shakespearean.

Whom does Prospero give favorable issue to? Placed at the head of the 1623 First Folio, Prospero’s “Tempest” gives issue to William Shakespeare the usurper as the “right” (rather than the “sinister”) “Duke of Milan”. This is probably why the play has caused Oxfordians so much grief – it was intended to prop up the new “Duke of Drowned Lands”, where Oxford’s broken staff has been drowned. (See The Devil is an Asse, Jonson’s 1616 farewell to William of Stratford.)

If Jonson had claimed it as his own, we would see in it a major turning point of his life. Though urged by friends to take revenge after the humiliation of Satiromastix, by 1611, he has at last forgiven “Captain Tucca” for all the trespasses against the order of goodfellowship he had endured at the Captain’s hands, from 1597 through 1602. Most scholars note a new air of forgiveness in Jonson’s work post-1611, when he finally comes back to the London stage in 1614 with Bartholomew Fair.

By giving The Tempest to William of Stratford instead of claiming responsibility for it, he kept his alchemical joke playing in perpetual motion for posterity, on stages across the Globe. Surely, he must have known that his gift to William at the expense of Edward would undercut his entire project, which was to choose forgiveness rather than vengeance. Sweet revenge, perfectly plotted, got the better of him.

Marie