Now available in paperback from Grove Press, with a new forward by James Norwood, Professor of Humanities, University of Minnesota:

Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom: the True History of Shakespeare and Elizabeth

by Charles Beauclerk

Grove Press, 2011

Now is this golden crown like a deep well

That owes two buckets, filling one another

The emptier ever dancing in the air

the other down, unseen, and full of water.

What makes a history of Shakespeare “true”? Charles Beauclerk’s story begins propitiously – he has the right man, Edward de Vere, and he knows that Edward de Vere drew from a deep, unfathomable well:

…the process of making images is largely unconscious, fashioned from the invisible components of the individual imagination, rather like an alphabet arising out of the unconscious of a new race. … In this hinterland of the soul, where images hatch, we are very close to the heartbeat of motivation, of sensing why an author writes as he does. (SLK, p. 156)

Remarkably, the author also knows his own part – and the part that every lover of Shakespeare’s poetry performs – when we set out to transcribe and interpret these heartbeats:

We respond to him on a preconscious level – between the lines – almost as if we were co-creators, for the dynamic field in which his unconscious mind intersects with ours is intensely alive, making his work strongly akin to music. (SLK p. 164)

This unconscious intersection with our will, powered by Shakespeare’s irresistibly mellifluous lines, is a form of magic. We can’t help wanting to take his words in, to have them “by heart”, to release them on our own breath. We are enchanted, and in this state, Shakespeare’s story – the one we read between the lines of his kings and queens and all their devastating follies – touches a part of us that makes us love him and want to protect him.

The facts of Edward de Vere’s troubled biography, placed alongside this poetry, vibrate through every synapse of the work, charging the lines, images and words with sparks of meaning. By the light of these shooting stars, like the bewitching glow of Ariel’s “flamed amazement” on the topmast of our brave vessel, we read and listen for his heartbeat, instead of our own.

But are these new signals yielding a “true” history of Shakespeare? Such a prodigious intelligence will not give up its mysteries to weekend stargazers. Like Dante, Shakespeare dared to write his autobiography in colossal cipher. Does Charles Beauclerk have the key to Shakespeare’s dramatic alphabet? I think he has one vital part of it. Towards the end of Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom, he tells us that “an essential quality of the plays themselves” is that “they are the life, not only of the dramatist, but of the times in which he lived. Their fabulousness is their reality.” (SLK p. 325) In other words – and I hope I do justice to what Charles intended here – Shakespeare’s plays and poems are fables. They may be populated with what seem to be real people from de Vere’s life, but their “reality” has been transformed into something necessary to the poet.

The truth of fables is not a literal truth, that we can prove or disprove with historical documents, but a psychic one, transferred from the poet to the heart and mind of the true listener. The fabulous subconscious story that Charles Beauclerk hears is in some ways the same story that Edward de Vere seems to be whispering in my ear, each time I go back and read The Collected Works of William Shakespeare cover to cover. This tragic tale has five essential components:

1. Shakespeare’s works betray a very personal, hyper-sensitivity to the stain of bastardy.

2. He thought of himself as a Prince, but along the way he lost his kingdom.

3. His poetic gift compelled him to transform the dross and agony of life into a surrogate kingdom of the mind.

4. His dramatic portrayals of Elizabeth suggest a privileged but volatile relationship.

5. “Shakespeare’s desire for vengeance was real and one of the great motivating forces of the canon.” (SLK, p. 274)

Even when one disagrees intensely – as I most emphatically do – with some of Charles Beauclerk’s basic assumptions and theories, the great wonder of his “true history” is how much of what he draws up from below the mottled surface scum of the well remains pertinent. One bucket – for supporting facts in the historical record, cautiously interpreted – is often the emptier, and dances in the air, but the other sinks deep, and fills with water. Beauclerk is extraordinarily attuned to Edward de Vere’s personal transformations of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, with a keen eye for permutations of the Actaeon myth. Here are a few examples of what you will miss, if in your aversion to Prince Tudor theory or insistence upon historiographical rigor you neglect to read Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom, as I almost did:

In another extraordinary resurfacing of the Actaeon myth, Tamora is compared to Diana, the moon goddess. When Lavinia and her husband, Bassianus, come upon Tamora in the woods, the empress tells Bassianus that had she Diana’s power she would mete out the same punishment to him that Actaeon suffered at the hands of the goddess. In the end, it is Lavinia who is fated to drink from this bitter cup, for like Actaeon transformed into a stag she loses the power of speech, and her delicate hands are turned into hooflike stumps.” (p. 273)

Titus is a play that I know quite well, but this searing vision of Lavinia as a silent stag was a revelation for me. Venturing into more heretical territory, Beauclerk offers a terrifying insight into the personal relevance of Shakespeare’s two published poems, Venus and Adonis and Rape of Lucrece:

Venus, who at the end of the previous poem flew off to Paphos, where she meant to “immure herself and not be seen,” is transformed into the chaste and cloistered Lucrece; and the boar-pierced Adonis becomes “lust-breathed” Tarquin, who in destroying the chastity of “the silver moon,” as Shakespeare describes Lucrece – i.e., in deflowering the goddess – brings down the monarchy. Thus Adonis becomes both the flower and the serpent under it. The flower that the goddess presses to her bosom is beautiful but deadly, rather like the asp that Cleopatra nurses at her breast. Thus the Shakespearean hero-archetype embodies within himself both the redeemer (Adonis) and the destroyer (Tarquin)… (p. 176)

“Thus Adonis becomes both the flower and the serpent”: I had suspected as much, but have never had the courage to raise this topic for discussion in the usual Oxfordian chat-rooms and other venues. In this, and in his recognition of Oxford’s vengeful nature, (quoted above), we seem to have witnessed the same disturbing basilisk, daring us to look in his eyes. Beauclerk doesn’t flinch; his commentary on Falstaff is chilling in its penetrating accuracy:

Ultimately, Falstaff is imprisoned in his own kingdom of language, where wit takes precedence over feeling. When he says that his womb undoes him, it is his womb of wit – his invention – rather than his great belly. Though wondrously humorous, the fat knight seems to have almost no feeling toward others; he is too wrapped up in the great adventure on which his great wit is willy-nilly leading him.

Now for our differences. They are many, but only one really matters: Who were Edward de Vere’s true parents? Charles Beauclerk’s history begins with the tentative proposition that Oxford was the child of Princess Elizabeth and Thomas Seymour. Note the word “tentative”, which I’ll get to in a moment. My position is that Edward was John de Vere’s firstborn son, but not securely legitimate, as the historical records show. The following brief essays, along with the file on the 1585 Depositions, outline the historical and literary basis for my alternative theory, that Joan Jockey may have been Edward’s true mother: John de Vere’s firstborn son; The Goddess of Justice; “Why dost not speak to me?”; “You bee a sort of knaves”, sayd Skelton; 1585 Depositions Concerning Oxford’s Legitimacy

When Beauclerk chose to build his story around the second Prince Tudor theory, surely he knew he was taking on a highly controversial and divisive premise. Disarmingly, with strategically placed deployments of “if” and “seems” and “whether… or not”, he allows for our hesitations and doubts: when all is said and done, perhaps we will not find that he has proven his hypothesis:

p. 41 “Whether she bore a child by Seymour or not…”

p. 92: “Thus, if Oxford was Elizabeth’s son…”

p. 101: “….like Hamlet he was, it seems, the son of the queen.”

p. 158: “And if his mother was the Virgin Queen…”

p. 224: “If Shakespeare was indeed the son of the Virgin Queen…”

p. 296: “Whether he was the queen’s son or not…”

p. 322: “… and Shakespeare, it seems, was the fruit of that trespass.”

p. 334: “…in Oxford’s case, if, as the evidence suggests, his mother was the most powerful woman…”

As Touchstone wittily puts it, “Your If is the only peace-maker; much virtue in If!”

Here’s an “if” in return: “If Edward de Vere knew for certain that he wasn’t John de Vere’s son, but instead, was the bastard son of Elizabeth Tudor and Thomas Seymour, how would he feel about the exchange?” On page 86, Beauclerk writes:

Whatever comforts he could press to his bosom Edward de Vere knew for certain that there were those about him who saw through his “Oxford” mask; nor could he draw solace from the fact that the blood of the Tudors flowed in his veins, for his royal birth was far from being a political reality. [emphasis added]

But beginning on p. 231, under the sub-heading “Tudor-Celtic Mythology”, he exposes the less-than-glamorous roots of the Tudor dynasty:

But beginning on p. 231, under the sub-heading “Tudor-Celtic Mythology”, he exposes the less-than-glamorous roots of the Tudor dynasty:

The Tudors were Welsh landowners… …In the Tudors we have a self-consciously created dynasty aware of their weak claim to the throne, who buttressed their credentials by tracing their line from King Arthur, the once and future king. In naming his firstborn son Arthur and having him christened at Winchester Cathedral, Henry VII was deliberately invoking the chivalry and glamour of Britain’s semi-mythical past, a considerable irony in view of his own grasping, ungenerous nature and his relentless undermining of the old feudal nobility. (SLK, p. 232)

Lest we forget, neither Edward Oxenford nor William Shakespeare ever wrote a play about Henry VII, whom Francis Bacon tells us severely undermined the 13th earl of Oxford’s power, in an apocryphal tale that sounds very much like one of madcap Ned de Vere’s bibulous inventions. Continuing his deconstruction of the Tudor Myth, Beauclerk writes:

The Tudors, in the grandiosity generated by their lineal insecurity, embraced the notion that they were the promised descendants of Arthur…

The Tudors, in the grandiosity generated by their lineal insecurity, embraced the notion that they were the promised descendants of Arthur…

Once on the throne, [Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond] played up the romantic image his deeds fostered in people’s minds. In truth, the Tudor dynasty was founded upon conquest (and the killing of a king).” “Despite his insistence that this was a reconquest, which avenged the original Saxon invasion, a deep insecurity accompanied the dynasty through its 118 years of rule. (p. 233)

Life for [Henry VIII] was theater; his every act invited a fanfare. Yet all this show masked a deep insecurity, which became more conspicuous as his reign ripened. (p. 235)

As pater patriae (father of his people) and supreme governor of the Church of England, Henry VIII invested the monarchy with a revitalized, almost mystical sense of its sovereignty, yet he was an imperialist in outlook. … His veneration for the traditions, music and architecture of the Catholic church sat uncomfortably with his desecration of the monasteries, and his love of chivalry and the joust contradicted his protracted attacks on the old feudal nobility. (p. 236)

Would the 17th earl of Oxford and Lord Great Chamberlain of England, whose ancestors came in with William the Conqueror, have drawn any solace from losing his de Vere blood in exchange for that of the insecure Tudors? I don’t think so.

In my reading of the evidence, both historical and literary, the earl of Oxford drew his sustaining identity from his claim to the ancient Vere line and their affinity. Their historical triumphs and quarrels were part of his legacy; their family traits were in his genetic makeup. If Nick Bottom’s “mythic DNA is the Minotaur, the monstrous son – half man, half bull – of Minos, King of Crete” (SLK, p. 202) then so too is this strain running in the veins of the man who signed himself Edward Oxenford. When he gazed upon the faces of the effigies that once graced Colne Priory, he was seeing his grandsires and grandams, and the faces of his own future heirs. As we read in Chapman’s eulogy of Oxford in The Revenge of Bussy D’Ambois:

…he had a face

Like one of the most ancient honour’d Romans

From whence his noblest family was deriv’d.

These were his people. If we lose sight of this, we lose our first and best contact with Edward de Vere and how he became “Shakespeare”. He loved his honor as a Vere; he owned his shame as a Vere; he wreaked his vengeance as a Vere:

…when Gloucester sees a beggar in the storm, he thinks a man a worm, and at that moment his son Edgar comes into his mind. Edgar, the outcast son, is the worm (worm in French being ver). When Cleopatra arranges to die in her monument, a clown enters with an asp – or worm, as he calls it – hidden in a basket of figs. (SLK p. 372)

“He that has a house to put’s head in has a good head-piece” (III.ii. 25-26)

.

Say, is my kingdom lost? why, ’twas my care

And what loss is it to be rid of care? ~ Richard II

I agree with Beauclerk that Shakespeare’s plays and poems bear witness to the pain of having lost a kingdom, but in my view, (derived in large measure from the political understory of the Howard family in Titus Andronicus) that kingdom was more likely to have been in opposition to the Tudor line than a part of it. On his own, Edward de Vere had three earthly kingdoms somewhat within his grasp, all of them lost by 1591. The first was a Plantagenet alliance through marriage to one of the Hastings girls, which Beauclerk mentions on p. 71: “It looks as though John de Vere had taken it into his head to arrange a royal marriage for his teenage charge…” The second was Oxford’s impetuous and near-treasonous support for his first cousin Thomas Howard, who lost his head over the hare-brained temptation to wed Mary, Queen of Scots.

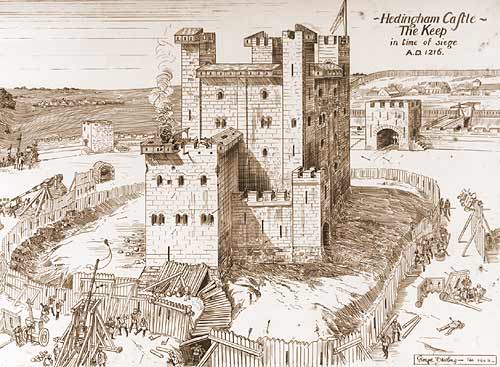

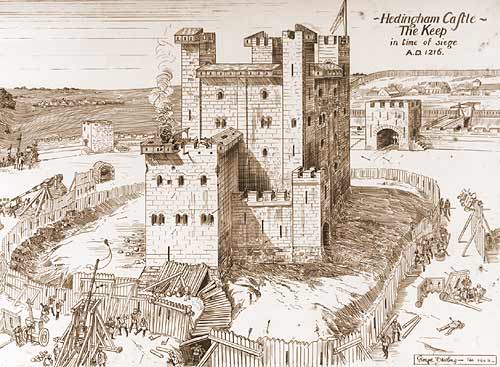

The third lost kingdom, as Beauclerk notes, was the ancient seat of the Oxford earldom: “Then in December 1591, …Oxford surrendered the heart of his de Vere inheritance by alienating Hedingham Castle to Burghley in trust for his three daughters. It was an abdication with rich consequences for literature, if King Lear is anything to judge by.” (p. 330) But why would a prince of the realm and poet who boldly tells the queen’s chief minister “I am that I am” have any need for a paltry scepter? Why would he be so foolish as to desire all the mundane distractions and obligations that turn a golden crown into a dull and heavy lump of lead? The true kingdom that Oxford strove mightily to maintain in his own sovereign control was that of the mind:

As James Kirsch says of Hamlet and his father, so might we say of Shakespeare and Elizabeth: his kingdom was the inner world, hers the political realm. (p. 295)

As in Hamlet, the only true king seems to be a ghost. Scratch the surface of these plays and one finds oneself staring at the crowned figure of vanity holding a skull in one hand and the fool’s bauble in the other. (p. 210-11)

As if he could not believe he had a true right to his inherited “kingdom” based in Essex, Oxford recklessly divested himself of all its physical trappings, till he had nothing to pass on but his name and his words. The first went to his heirs of the blood, the second to his heirs of the spirit, an awesomely potent bequest that we still haven’t learned quite how to decipher. The quest is daunting, too much for one lonely reader, or a whole fraternity of stargazers, to take on. How can we bear to follow King Lear on his journey out into the raging tempest that mirrors the demons in his skull, once we know that he is not a stage puppet but a breathing portrait of the author, and the purified condensation of everything that the name “Shakespeare” calls up in our hearts and minds? The jewel in the crown of Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom is Beauclerk’s courageous attempt to do just that:

Opening one’s heart to a great work of literature of the intensity of King Lear is like setting forth on a pilgrimage toward an inner realm on the horizon of one’s being. Reading and walking, if undertaken in the spirit of wonder and intrepidity that transforms them into a way of life, refresh the soul in profound and allied ways. Thoreau’s advice to walkers would be my advice to Shakespeare’s readers: “We should go forth on the shortest walk, perchance, in the spirit of undying adventure, never to return – prepared to send back our embalmed hearts only as relics to our desolate kingdoms.” As a work that shakes the foundations of western culture, King Lear demands this sort of self-abandonment. We never quite return from the journey.

My copy of Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom has furious scribbles in the margins of every other page, some of them less than polite. Yet when I told Charles Beauclerk in no uncertain terms that I could not agree with his theory on Oxford’s birth, he was most gracious, replying that he is open to hearing other theories; would I send him a copy when I write up my thoughts? His True History of Shakespeare and Elizabeth may not be your cup of true, but it is certainly the work of a generous and intrepid spirit. ~Marie Merkel

Recent Comments