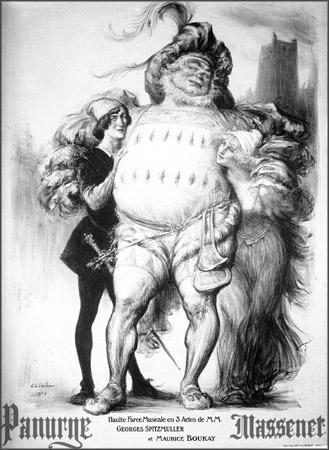

Sir John Falstaff vs. Lean Macilente

“A Movable Feast: The Liturgical Symbolism and Design of The Tempest“

“A Movable Feast: The Liturgical Symbolism and Design of The Tempest“

by Roger Stritmatter and Lynne Kositsky

Shakespeare Yearbook, Vol. XVII, 2010

So much depends on an impossible-to-answer question: When was The Tempest written? Oxfordian scholars Roger Stritmatter and Lynne Kositsky have just posted what they believe to be “the most important” in their series of published articles challenging the assumption that Shakespeare wrote The Tempest not long before Hallowmas night, 1611, when The King’s Men performed a play by that name for James and his court at Whitehall.

I agree. This is the most important of the six pieces that Stritmatter and Kositsky have so far published, for the delightful reason that it’s the first in which they’ve allowed Ben Jonson his place within The Tempest’s rarefied circle of “measured harmonies”. As a specialist who “understands [the paradoxical merging of pleasure and virtue]”, Jonson even earns a spot in their concluding paragraph:

Evidence adduced in the present essay shows that both the symbolism and design of The Tempest are explicable on the premise that the play was written for a Shrovetide performance. Indeed, so rich and detailed are the associations between Shrovetide and Lenten practices and the design of Shakespeare’s play that it may safely be concluded that it was in fact written, as R. Christopher Hassel has said of Jonson’s epiphany masques and Twelfth Night, “with the major outlines of the festival season firmly in mind”.

Once again, I agree, but this time with a few reservations. For all we know, The Tempest may not have been written specifically for an upcoming Shrovetide performance, such as that on “Shrovmonday” of 1604/5, when The Spanish Maze appeared and then disappeared. And the play’s undercurrent of Lenten imagery doesn’t necessarily rule out its necromantic relevance to a Hallowmas night performance. This seems to me the weakest portion of their essay, with insufficient quotations from the scholars whose theories they dismiss as “incorrect”, and no mention of John B. Bender’s essay, “The Day of the Tempest” (ELH, 1980). Nevertheless, I do think that the authors have tapped into an aspect of the play’s allegoric design that now seems incredibly obvious, after they’ve pointed out the clues. Here’s one vivid example:

Among the most popular emblems of the season was Jack-a-Lent, a puppet made from a Leek and a Herring and set up on Ash Wednesday as a scapegoat for the deprivations experienced at Lent. Decorated with herrings, and pelted with missiles he became “both a manifest and a ubiquitous symbol of the long period of austerity and at the same [time?] operated as a kind of safety valve.” Caliban’s likeness to this “ubiquitous” Lenten scapegoat, half man and half fish, hardly requires emphasis.

If, indeed, the author saturated his scenes with Shrovetide and Lenten imagery and philosophy, how does this fresh insight affect our view of The Tempest from the Oxfordian perspective?

If, indeed, the author saturated his scenes with Shrovetide and Lenten imagery and philosophy, how does this fresh insight affect our view of The Tempest from the Oxfordian perspective?

The answer isn’t immediately apparent in “A Moveable Feast”, since Stritmatter and Kositsky’s arguments for a Shrovetide-Tempest never require a mention of Edward de Vere. “Shakespeare’s” great rival, however, just happens to come in for a lion’s share of their Shrovetide references. When collected in one place, Ben Jonson’s résumé in the field of Shrovetide and Lenten entertainment and commentary is quite impressive, as witnessed by these quotes from “A Moveable Feast”:

On p. 338:

“In Time Vindicated (1622) Ben Jonson has Fame denounce “lawless Prentices, on Shrove Tuesday” who “compel the Time to serve their riot:/ for drunken Wakes and strutting Beare-baitings, that savour only of their own abuses.”

On p. 346, a reference to The Haddington Masque:

…the title page of Ben Jonson’s 1608 Shrovetide production celebrating the wedding of Viscount Haddington to Lady Elizabeth Ratcliffe, illustrates the traditional association” [of Shrovetide and marriage masques].

In footnote 41, p. 366:

Jonson’s Chloridia, a 1630 Shrovetide masque [which, like The Tempest] also features Juno and Iris as prominent characters.

In footnote 63, p. 368:

The prologue to Staple of News, a play thought to have been written for Shrovetide, emphasizes the connection between the festival and “merrymaking”: “I am Mirth, the daughter of Christmas, and Spirit of Shrovetide. They say, It’s merry when Gossips meet; I hope your Play will be a merry one!

In footnote 91, p. 370:

The association between Shrovetide and the labyrinth is conventional in early modern drama and would have been readily recognized by Shakespeare’s audience. Daedalus even appears as the narrative voice of Jonson’s Shrovetide masque, For the Honour of Wales, constructing a knot so cunningly interwoven that “ev’n th’observer scarce may know/Which lines are pleasure’s and which are not” (225-27) and R. Chris Hassel calls him the “most important interpreter of the Shrovetide festivities” (132) , one who “understands [the paradoxical merging of pleasure and virtue] better than any …subsequent interpreters of this Shrovetide tradition” (129).

One play NOT mentioned by the authors, but with immense relevance to any study of Edward de Vere and/or The Tempest, is Jonson’s Every Man Out of His Humor. Not only do we find Jonson building his plot within a merry Shrovetide context, but in the 1601 Quarto of the play, the rascal slyly hitches his play to the turnip-cart of Shakespeare’s Gargantuan hero:

One play NOT mentioned by the authors, but with immense relevance to any study of Edward de Vere and/or The Tempest, is Jonson’s Every Man Out of His Humor. Not only do we find Jonson building his plot within a merry Shrovetide context, but in the 1601 Quarto of the play, the rascal slyly hitches his play to the turnip-cart of Shakespeare’s Gargantuan hero:

Marry, I will not do as Plautus, in his Amphitryo, for all this: Summi Iovis causa, plaudite: beg a plaudit for god’s sake. But if you (out of the bounty of your good liking) will bestow it, why, you may (in time) make lean Macilente as fat as Sir John Falstaff.

The evidence offered in “A Moveable Feast” puts a new spin on this passage. What does Shakespeare’s fat Falstaff represent for Ben Jonson, and his lean and mean Macilente? The excess of Carnival vs. the sobriety of Lent? Purses swollen by the hilarious misrule of London’s infamous “Vice” vs. the empty pockets and hungry rumblings of a Virtuous Poet? Sir Epicure Mammon vs. Surly Caliban? Subtle the Alchemist vs. Prospero? Once again, whether we want him or not, Ben Jonson offers himself as the savviest guide to the mysteries of The Tempest.

~*~*~

NOTE: Two small errors that the authors may wish to correct in their online text: “6 Nov. 1611” as the date for the first recorded performance of The Tempest (p. 341) and the attribution to Sebastian of Antonio’s very strange and final words of the play: “A plain fish, and no doubt marketable.” (p. 345-6)

Recent Comments