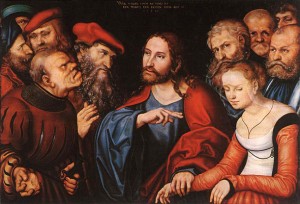

“Why dost not speak to me?”

Why dost not speak to me?

Alas, a crimson River of warm blood,

Like to a bubbling Fountain stirred with wind,

Doth rise and fall between thy Rosed lips,

Coming and going with thy honied breath.

But sure some Tereus hath deflowered thee,

And lest thou shouldst detect them cut thy tongue.

Without her saying a word, Marcus already knows an unspeakable shame has befallen his niece. “And lest thou shouldst detect them” he says; he knows that she’s been attacked by more than one Tereus, and knows that the blood he sees on her face comes from a cut tongue.

Yet nothing in the play gives us any reason to suspect him of complicity in the crime – quite the opposite. Throughout the furies of bloody vengeance, Marcus remains a totem of noble, compassionate stability. He knows more than he should simply because his creator is not offering realistic drama, but a stylized pageantry of mythic revenge. “Shakespeare”, in the person of Uncle Marcus, speaks like a young poet stumbling through a textbook translation of brute and nasty fact into beautified, exalted truth.

Some truths are too horrifying, or embarrassing, or dangerous to speak of, except through the shimmering veils of poetry or the grotesques of old wives’ tales. Richard Enowes’ confessed crime of 1585 falls into this category. Forty years pass before even a whisper of this callous gang rape surfaces in the records, and even that document leaves us with more questions than answers. When did John de Vere learn of the attack on Joan? When, if ever, did he discover who was responsible? If he’d known that his sister Anne’s husband, Edmund Sheffield, and his sister Elizabeth’s husband, Thomas Darcy, had organized the assault, would he have chosen to remain silent rather than accuse his own kinsman and shame his family name? Could he possibly have known all along just what they were up to? As Alan Nelson observes:

The 16th Earl’s exact role in the attack on Joan Jockey is uncertain. Either his two brothers-in-law acted to destroy an alliance that they regarded as a threat to their own interests; or the Earl cooperated in an effort to drive away a woman who had become a liability. That the Earl was somehow complicit is suggested by the fact that Enowes and Smith stayed in his service, as revealed by the Earl’s will of 1562, while he remained on exceedingly good terms with Darcy, as revealed in his will of 1552.

When I first read this, it seemed to me that Nelson’s bias against Edward de Vere’s person had unfairly spilled over to the father. He starts out on firm footing, recognizing the benefits of a potential new alliance to Darcy and Sheffield. But then he neglects to examine other possible reasons for Earl John’s continued employment of Enowes and Smith, or the full, coercive context of those “good terms with Darcy”. No where in his account do we learn of Earl John’s shattering loss of another brother-in-law, Henry Howard, beheaded in the midst of his erratic marriages. Perhaps one needs to have lived in terror to recognize when others are manifesting the strains of life under a tyrant.

Truth to tell, my own response to the 1585 depositions has been equally biased. In my earliest phase of writing about Titus Andronicus from an Oxfordian perspective, I was too ready to interpret “Shakespeare’s” dramatization of a similar rape, and how Uncle Marcus responds, as evidence of how the real author, Edward Oxenford, knew his father had reacted to the assault on Joan. The lines I’ve quoted above, along with so much of the play, seemed to me a wonderfully compassionate record of his father’s helpless fury over what his in-laws had done. But for all we know, Oxford had never heard of Joan Jockey before 1585.

Truth to tell, my own response to the 1585 depositions has been equally biased. In my earliest phase of writing about Titus Andronicus from an Oxfordian perspective, I was too ready to interpret “Shakespeare’s” dramatization of a similar rape, and how Uncle Marcus responds, as evidence of how the real author, Edward Oxenford, knew his father had reacted to the assault on Joan. The lines I’ve quoted above, along with so much of the play, seemed to me a wonderfully compassionate record of his father’s helpless fury over what his in-laws had done. But for all we know, Oxford had never heard of Joan Jockey before 1585.

How would a trained historian approach the evidence, both documentary and literary? It seems to me that any account of Oxford’s life must begin with a clear, emotionally detached – left-brained if you will – assessment of the documents, before flying aloft with right-brain intuitions of a deeper, camouflaged truth. I now know that my own first, second and third readings of the 1585 depositions failed to pick up many small hints and inconsistencies within the five different accounts. The layout of the document made it very difficult (for me at least) to keep track of what question each man was answering, and who said what before and after him, in response to the same question. For ease of comprehension, I’ve now reformatted the questions and answers, and posted what I hope will be a more reader-friendly version: 1585 Depositions Concerning Oxford’s Legitmacy. [filed under “The Life”, top menu]

In two earlier posts, “John de Vere’s firstborn son” and “The Goddess of Justice“, I’ve been laying the groundwork for an in-depth re-examination of every piece of evidence relevant to Oxford’s birth. In the next few weeks, I’ll be reviewing six different summaries of what the 1585 depositions actually say:

1. Alan H. Nelson, who gives the fullest account of the Joan Jockey incident on pp. 14-19 of Monstrous Adversary (2003).

2. Daphne Pearson, who briefly discusses Oxford’s legitimacy problems on pg. 25 and on pg. 112 of Edward de Vere (1550-1604): The Crisis and Consequences of Wardship (2005).

3. Mark Anderson, who talks about John de Vere and his marriage problems on pg. 3 and discusses the”bastardy lawsuit” of 1563 on pg. 24 of Shakespeare by Another Name (2005).

4. Charles Beauclerk, who summarizes these claims of illegitimacy on pp. 56-7 of Shakespeare’s Lost Kingdom (2010).

5. Christopher Paul, whose article, “The ‘Prince Tudor” Dilemma: Hip Thesis, Hypothesis, or Old Wives’ Tale?” is frequently cited as a rebuttal to adventurous theories about Oxford’s birth.

6. Nina Green, who deftly summarizes the 1585 Depositions; mentions the issue in the footnotes to her 2009 Brief Chronicles article, “The Fall of the House of Oxford”, and again in her Oxmyth’s involving other individuals page, where she lists as “Myth” the assertion that “the 16th Earl’s second marriage, to Margery Golding, was ‘irregular’.”

If you know of an important discussion of this document that I’ve overlooked, whether published in a book, journal, newsletter or online, please send me a message so I can include it in this survey. Many thanks!

Why dost not speak to me?

Alas, a crimson River of warm blood,

Like to a bubbling Fountain stirred with wind,

Doth rise and fall between thy Rosed lips,

Coming and going with thy honied breath.

But sure some Tereus hath deflowered thee,

And lest thou shouldst detect them cut thy tongue.

Recent Comments