Who Wrote Prospero’s Epilogue?

…Now I want

Spirits to enforce: Art to inchant,

And my ending is despaire,

Unlesse I be reliev’d by praier

Which pierces so, that it assaults

Mercy it selfe, and frees all faults.

As you from crimes would pardon’d be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

For sure, the quality of mercy has a trembling, “unmistakable” resonance in the works of Shakespeare. Nevertheless, when we exit the maze of The Tempest, floating on Prospero’s astoundingly Catholic epilogue, with the words “mercy“, “crimes” and “pardon” resounding in our ears, chances are that the artisan responsible for our euphoria was Ben Jonson. In my view, Jonson trumps everyone as the best candidate for the epilogue’s exercise in octosyllabic couplets, which he used to such touching effect in his elegy “On My First Daughter“. The evidence is, of course, circumstantial, but strong on both the biographical and literary fronts:

…Help, O you that may

Alone lend succours, and this fury stay.

Offended mistress, you are yet so fair,

As light breaks from you that affrights despair,

And fills my powers with persuading joy,

That you should be too noble to destroy.

There may some face or menace of a storm

Look forth, but cannot last in such a form.

If there be nothing worthy you can see

Of graces, or your mercy here in me,

Spare your own goodness yet; and be not great

In will and power, only to defeat.

God and the good know to forgive and save;

The ignorant and fools no pity have.

I will not stand to justify my fault,

Or lay th’ excuse upon the vintner’s vault;

Or in confessing of the crime be nice,

Or go about to countenance the vice,

By naming in what company ‘twas in,

As I would urge authority for sin;

No, I will stand arraign’d and cast, to be

The subject of your grace in pardoning me,

And (styled your mercy’s creature) will live more,

Your honour now, than your disgrace before…

The link between “fault” and “crime” is a natural one, of course; Shakespeare has it here and there. But in Jonson’s case, he left us an autobiographical poetic essay which shows their deep resonance for him. In 1602, he linked these two words in his postscript “To The Reader“, when protesting against those unnamed individuals who took offense to his Poetaster:

The link between “fault” and “crime” is a natural one, of course; Shakespeare has it here and there. But in Jonson’s case, he left us an autobiographical poetic essay which shows their deep resonance for him. In 1602, he linked these two words in his postscript “To The Reader“, when protesting against those unnamed individuals who took offense to his Poetaster:

“Nor was there in it any circumstance

Which, in the setting down, I could suspect

Might be perverted by an enemy’s tongue;

Only it had the fault to be call’d mine;

That was the crime.”

Can you imagine if the miraculous Tempest had suffered the “fault” to be called “Ben: Jonson’s”? Would anyone ever have perceived it as sublime?

3. JONSON ACTIVELY SOUGHT MERCY THAT WOULD SET HIM FREE: In 1605, while in prison due to the King’s wrath over some objectionable matter in Eastward Ho!, Ben Jonson wrote letters which document this harrowing moment in his life, including a humble plea for the king’s mercy:

“I speak not this with any spirit of contumacy, for I know there is no subject hath so safe an Innocence, but may rejoyce to stand justified in sight of his Soveraignes mercie. To which we must humblie submytt our selves, our lives and fortunes”.

In another letter written at this time, we find him still highly aggrieved by the supposed “faults” and “crimes” that others have found in his literary works:

“I beseech your most honorable lordship, suffer not other men’s errors or faults past to be made my crimes; but let me be examined both by all my works past and this present…”

4. JONSON PIONEERED THE EPILOGUE-SPOKEN-IN-CHARACTER: As Stephen Orgel observes in his edition of The Tempest, “Prospero’s epilogue is unique in the Shakespeare canon in that its speaker declares himself not an actor in a play but a character in a fiction.”

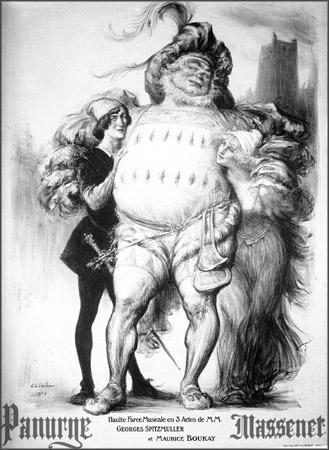

Unique perhaps for Shakespeare’s Tempest (pub. 1623), but not for Ben Jonson (as Orgel should know!), who has his “Fox” step forward to speak for himself, in character, at the end of Volpone (pub. 1606). Again, in The Tempest’s inverted twin, The Alchemist (pub. 1612), we find that Jonson has his linked pair of master and servant, “Lovewit” and “Face”, speak the epilogue in character.

~ Marie Merkel

[edited on 2/25/15; new research and conclusion in the works]

Recent Comments