Shakespeare’s True Face

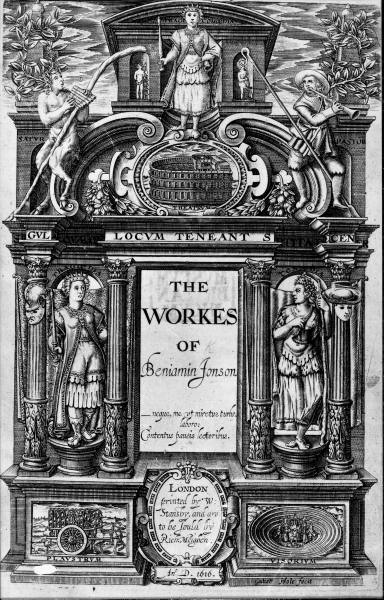

Almost no one is pleased by Martin Droeshout’s engraving of our beloved “Star of Poets”. Here’s the anonymous opinion of a writer for The Sun, reviewing Basil Brown’s Supposed Caricature of the Droeshout:

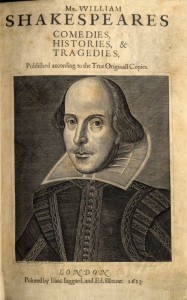

The abominable eidolon which appears in the First Folio, opposite BEN JONSON’S sly advice to the Reader to look rather upon the Booke than upon the picture, has been for nearly three hundred years the despair of everybody wondering what SHAKESPEARE’S physiognomy really was like. No human being ever even faintly resembled the Droeshout print. The face is as impossible as is the doublet of riveted boiler iron. ~Feb. 23, 1911, The Sun

Much to be preferred would have been something more closely modeled on the movie-star handsome face in the Cobbe Portrait, or the immediately likable fellow teasing us with his ever-so-sweet-and-shy smile in the Sanders portrait.

Dream on, my friends. Ben Jonson, who surely knew “The AVTHOR”, says this is our man:

TO THE READER:

This figure, that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut;

Wherein the Graver had a strife

with Nature, to out-doo the life:

O, could he but have drawne his wit

As well in brasse, as he hath hit

His face; the Print would then surpasse

All, that was ever writ in brasse.

But, since he cannot, Reader, looke

Not on his Picture, but his Booke.

Is Honest Ben playing with us? As a shrewd observer of his own times, and passionate imbiber of classic and continental literature, he’s our best contemporary witness to what the real “Shakespeare” – whoever you believe that may be – looked like, inside and out. After all, these two enormous poetic egos haunted the same London taverns and bookstalls. They wrote their comedies and tragedies for the same actors. Both were born poets, as well as “made”.

In the 1590s, both collaborated with that irrepressible satirist, Thomas Nashe. And both knew Francis Langley, lord of the manor of Paris Garden and owner of the magnificent Swan Theater. But there was one significant difference in each man’s recorded acquaintance with this pugnacious entrepreneur. William Shakespeare and his side-kick Langley were never arrested for their threats of bodily harm to William Wayte in 1596. A year later, however, Ben Jonson went to prison for his part in writing the disastrous Isle of Dogs, which played at Langley’s Swan. Soon after, the Poetomachia began, during which Shakespeare gave Jonson that famous, if elusive, literary purge.

No doubt about it, Ben knew our Author, and had reason to envy, and even resent him. When he assures us that the figure we see gracing Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies was “cut” for “gentle Shakespeare”, he speaks from a uniquely privileged position. We sense that he expects posterity will know this, and thus take him at his word. With a poetic genius of Jonson’s caliber, however, taking him “at his word” requires us to enter his own peculiar labyrinth of associative language.

No doubt about it, Ben knew our Author, and had reason to envy, and even resent him. When he assures us that the figure we see gracing Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies was “cut” for “gentle Shakespeare”, he speaks from a uniquely privileged position. We sense that he expects posterity will know this, and thus take him at his word. With a poetic genius of Jonson’s caliber, however, taking him “at his word” requires us to enter his own peculiar labyrinth of associative language.

Just as we do today, Jacobean followers of Jonson’s irreverent parodies would have sifted his contribution to the First Folio for the inevitable left-handed compliment to the master. For example, why, in such a short piece of verse, does Jonson use the word “brass” twice? As I’ve learned by following one of the most brilliant Oxfordian researchers we have, by the time the word “brass” works its way through Jonson’s literary digestive tract, he’s wholly transformed its surface connotations.

Since 2002, Nicole Doyle has been sharing her insights into the mysteries of the Droeshout engraving – from its mismatched eyes to its “impossible doublet” – with members of the late Robert Brazil’s Elizaforum. By placing these visual puzzles alongside Jonson’s words, both in the poems he wrote for Shakespeare in 1623 and where he’s used them in other works, she has shown – persuasively, in my view – that Jonson intended the reader to “read” Droeshout’s disproportionate engraving as an emblem of Shakespeare’s deformed literary “manners”.

For Oxfordians, this means that Droeshout wasn’t hired to cut a mockery of “the Stratford Man”. His model – and Jonson’s target – was “The AVTHOR”, whom Jonson belatedly embraces as “his beloved” for this grand occasion. What we are seeing in this iconic emblem isn’t Edward de Vere as he saw himself in the mirror, or the achingly human and noble being he made of himself in his art, but Edward de Vere through Ben Jonson’s eyes: sans Right, sans Romance, sans Idolatry.

Most likely, Martin Droeshout began his task with an image already in existence, as the British Museum’s website explains:

An engraving is not worked directly from life, but from a flat model, either a painting or a drawing. Droeshout must have been given a painting or drawing of Shakespeare as a young man, from which to engrave his plate.

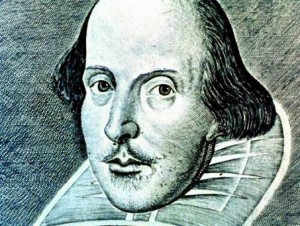

Since Oxfordians do possess the advantage of a painting or two of our “Shakespeare as a young man” – one when he was twenty-four or so, and the other from when he was in his early thirties – we can readily compare these relatively honest (if not flattering) images of Edward de Vere with the First Folio’s satiric cartoon. Here they are, left and right profile, side by side with Droeshout’s engraving:

.

.

After viewing the Welbeck Portrait (top, right) in 1920, J. T. Looney suggested that:

…a very strong case might be made out for Droeshout having worked from this portrait, of Edward de Vere, making modifications according to instructions.

(Appendix II of Shakespeare Identified).

What do you think?

~Marie Merkel

This Figure, that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut,

Wherein the Graver had a strife

with Nature, to out-doo the life :

O, could he but have drawne his wit

As well in brasse, as he hath hit

His face ; the Print would then surpasse

All, that was ever writ in brasse.

But, since he cannot, Reader, looke

Not on his Picture, but his Booke.

Wow! This way, Oxford as in the Wellbeck can fit right behind the Droeshout mask, with his own real eyes peering out…? Great job, Marie!

Nice comparisons, Marie. Thanks. It’s also been noticed that Ben Jonson said the engraving was cut FOR “gentle Shakespeare” not OF him. The word “gentle” is also an example of Ben’s penchant for ambiguity. “Sweet Swan” is ambiguous, too, since a swan is usually mute, and it’s a symbol of royalty.

I believe that Ben knew exactly what he was doing, and that he wrote the tributes to Shakespeare signed by the actors in the First Folio. Clever, isn’t he?

Hugs from Helen

Thanks, Helen! Yes, Ben’s use of the word “FOR” rather than “OF” is curious, although that may have been somewhat innocent, given the short lines of the verse. Another very clever man, George Greenwood makes the case for Jonson’s ghost writing of the Heminges and Condell letter. His book Ben Jonson and Shakespeare is now available online.

Marie, This is brilliant. In all the stratforgeries, this best fits the most likely scenario*. You are helping us to get further inside of Ben’s head than I thought possible. From your balloon basket (with atomic telescope), can you tell us whether Ben himself knew what he was really doing? I ask this because much of what we know about his own creative life would end up today in a New Yorker review as “an unmade bed”.

Thanks for this insight, and for your delicious Site. Joe

* scenario = what we non-scholars use to stay in contact with whosoeVER he was/is. J

Thank you, Joe! Yes, I do think that Ben knew exactly what he was doing. “Unmade bed” he may seem by the biographical details, but his Art (with a capital “A”, always!) shows a poet who is ever alert to himself as the creator and observer within whatever fiction he’s creating. And that extends to those he observed, and parodied, as well. He sure had a lot of fun in his lampoons of Oxford – which the Lord Great Cham himself may have smiled upon – or not.