Since Hamlet will not be bounded in a nutshell, where does one start in tabulating parallels to this king of infinite space? We may as well begin with J. T. Looney’s Shakespeare Identified [1920], since Hamlet is so central to Looney’s thesis. What follows are 16 correspondences or allusions he found within Hamlet to situations in Edward de Vere’s life, each of these mentioned in passing, as part of his case for Oxford as Shakespeare. Not included in this post are those he reserved for discussion in Chapter XVI, “Dramatic Self-revelation: Hamlet”.

I’ve arranged Looney’s suggested parallels according to their approximate appearance within the play as it unfolds, with links provided to the text when available through Google books. In many cases, the excerpts I’ve provided give only a hint of the more complex associations that Looney is envisioning. The preliminary list below gives a brief title to each item, followed with a question mark to indicate a status of “to be debated” rather than “proven”.

Before debate on the merits of each item, however, it would be most helpful to consider the types of connections Looney has offered, the method he uses to deduce and support each parallel, and the quality of documentary evidence provided. It may be that some of Looney’s suggestions fall outside the parameters of this project.

1. I. i. 70-78: Allusion to the Armada?

2. I. ii. 58-61;112-16: EO & Hamlet both denied permission to travel?

3. I. ii. 187: EO & Hamlet both exhibit father-worship?

4. I. iii. 18: EO & Hamlet both could not marry as they chose?

5. II. i. 1-74: Burghley & Polonius both spied on their sons?

6. II. i. 58: Burghley & Polonius both wise about tennis court quarrels?

7. II. ii. 398-405: Hamlet’s jest to Polonius re: “Jephthah” fits Burghley’s sacrifice of Anne?

8. II. ii. 356 (and more): Hamlet w/players mirrors Oxford w/poets & his troupe?

9. III. i. 39-40 (and more): Social status of Cecil & Anne mirrors Polonius & Ophelia?

10. III. i. 90-150: Hamlet sees Ophelia as her father’s pawn mirrors EO and Anne Cecil?

11. III. ii. 91-2: Hamlet to Polonius on “university”/EO’s slight attendance?

12. III. iv. 24: Hamlet stabs Polonius, EO stabs Bricknell?

13. V. i. 60-4: Song from Lord Vaux of special significance for EO?

14. V. i. 75-7: Hamlet & Oxford both exhibit contempt for politicians?

15. V. ii. 1-81: Hamlet & EO both return from sea to the death of lover/wife?

16. V. ii. 291-3; 299-302: Hamlet’s “wounded name”> the “unlifted shadow” o’er EO’s name?

Relevant excerpts from Looney’s Shakespeare Identified

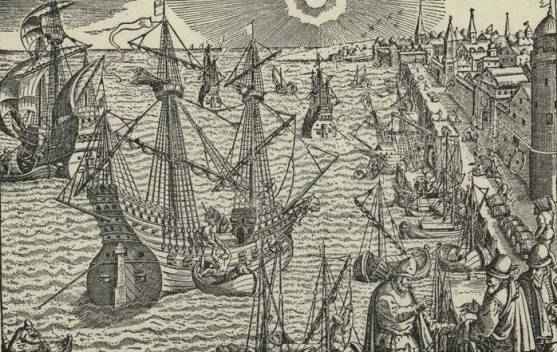

1) Act I. i. 70-78: “This same strict and most observant watch”

In February, 1587, Mary Queen of Scots was beheaded, and this is the year in which we lose traces of Edward de Vere’s connection with drama. It was a time of great stress and excitement in the country. The fear of a Spanish invasion lay heavily on the nation and preparations were in full swing to meet the expected Armada. Passing, as we of these days have done, through times of still greater stress, we can now quite see the allusion to England prior to the coming of the Armada in the following passage from Hamlet.

Tell me, he that knows,

Why this same strict and most observant watch

So nightly toils the subject of the land;

And why such daily cast of brazen cannon,

And foreign mart for implements of war;

Why such impress of shipwrights, whose sore task

Does not divide the Sunday from the week;

What might be toward, that this sweaty haste

Doth make the night joint labourer with the day?[p. 360]

2) Act I. ii. 58-61;112-16: “He hath, my lord, wrung from me my slow leave”

The special point with which we are now dealing — the obstacles thrown in the way of a young man’s wish to travel — appears again in “Hamlet.” Laertes applies for the king’s permission to go abroad, and the king asks, “Have you your father’s leave? What says Polonius?” To which Polonius replies:

He hath, my lord, wrung from me my slow leave

By laboursome petition, and at last

Upon his will I seal’d my hard consent:

I do beseech you, give him leave to go.

Then there is the king and queen’s opposition to Hamlet’s wish to go to Wittenberg, and the false reasons assigned:

King:

It is most retrograde to our desire;

And we beseech you, bend you to remain

Here in the cheer and comfort of our eye,

Our chiefest courtier, cousin, and our son.

Again we notice that it is Polonius who is chiefly opposed to his son’s travelling, exactly as Burleigh raised his own opposition into a settled maxim of policy:

Suffer not thy sons to cross the Alps and if by travel they get a few broken languages they shall profit them nothing more than to have one meat served up in divers dishes.

(Burleigh’s maxims – Martin A. S. Hume.) [p. 267]

3) Act I. ii. 187: “I shall not look upon his like again”

…The loss of such a father, with the complete upsetting of his young life that it immediately involved, must have been a great grief to one so sensitively constituted. We may naturally suppose, then, that the figure of a hero-father would live in his imagination; and the reader of “Shakespeare” who has missed this note of father-worship in the great dramas has been found wanting in serious attention to their finer contents.

The greatest play of Shakespeare’s, “Hamlet,” has father-worship as its prime motive:

“He was a man, take him for all in all,

I shall not look upon his like again.” [pg. 232]

4) Act I. iii. 18: “For he himself is subject to his birth”

We have already had to draw attention to the startling character of the analogy between Oxford and the central character in “All’s Well,” the royal ward, Bertram Count of Roussilon, to which must now be added this proximity in social rank and intimate intercourse with royalty, to which Helena refers in her conversation with the King. It will be interesting to notice, too, the emphasis given both in this play and in “Hamlet” to the idea that by virtue of their birth the chief characters had no personal liberty of choice in the matter of marriage. [p. 247]

5) Act II. i. 1-74: “Before you visit him, … make inquiry of his behaviour.”

It is quite evident, moreover, from G. Ravenscroft Dennis’s work on “The House of Cecil,” that when his eldest son, Thomas, afterwards Earl of Exeter, was in Paris, Burleigh had him watched and secretly reported on, quite in the manner of Polonius’s employment of the spy Reynaldo. [p. 261]

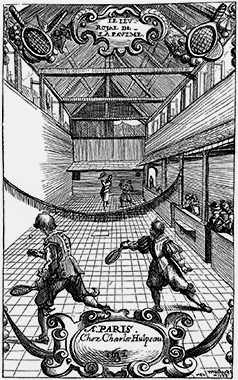

6) Act II. i. 58: “…there falling out at tennis”

The story of the tennis-court quarrel is one of the few particulars about Oxford that have become current. Indeed, one very interesting history of English literature mentions the incident, and ignores the fact that the earl was at all concerned with literature. Now, considering the prominence given to this story, it almost appears as if “Shakespeare,” in “Hamlet,” had intended to furnish a clue to his identity when he represents Polonius dragging in a reference to young men “falling out at tennis.” [pp. 296-7]

7) Act II. ii. 398-405: “O Jephthah, judge of Israel, what a treasure thou hadst!”

If, therefore, there is any character in Shakespeare’s works whom we may be able to identify with Burleigh, to have had him likened to Jephtha, as Hamlet does Polonius, would have been something of a slander upon Jephtha. For the conduct of this Old Testament character towards his daughter seems quite respectable compared with the sordid dealings of the great Lord Burleigh; and the tears which the latter seems ostentatiously to have shed at the death of her whom he called his “filia carissima” ought to have sprung from the grief of shame and repentance rather than the grief of bereavement. [p. 258]

8) Act II. ii. 356: “Do the boys carry it away?”

Although other companies of actors are referred to as “Boys,” it is to Oxford’s company that the name seems to have been most particularly attached. This frequent reference to his company as “The Oxford Boys” is suggestive, too, of a personal familiarity, and the kindly interest of an employer in the needs and welfare of the men he employed. From every indication we have of his character he was not the man to keep his gold “continually imprisoned in his bags,” to use his own phrase, whilst there were playwrights or actors about him whom he could benefit. Everything betokens a relationship similar to that which had existed between Hamlet and his players, and which he expresses in his welcome to them on renewing his intercourse with them:

“You are welcome, masters; welcome all. I am glad to see thee well. Welcome good friends. O! my old friend.”

Then there is Hamlet’s admonition to Polonius:

“Good my lord, will you see the players well bestowed? Do you hear, let them be well used … Use them after your own honour and dignity: the less they deserve the more merit is in your bounty.”

Seeing, moreover, that Oxford’s company has passed into the history of English drama as the “Oxford Boys,” what shall we make of Hamlet speaking of his company as “the boys”?

“Do the boys carry it away?”

More important, however, are the instructions and criticism which Hamlet as a patron of playactors offers, to his company. His whole attitude is just such as a patron of Oxford’s social position, literary taste, and dramatic enthusiasm would naturally assume towards a company which he was not only patronising but directing. In this matter no quotation of passages would suffice for our purpose. We can only ask the reader, bearing in mind all we have been able to lay before him, of Oxford’s poetic work, life and character, to read through the whole of that part of the play which treats of Hamlet’s dealing with the players (Acts II. and III. s. 2). If he does not feel that we have here an exact representation of what Oxford’s handling of his own company would be, our own work in these pages must have been most imperfectly performed. [p. 318]

9) Act III. i. 39-40: “And for your part, Ophelia, I do wish/That your good beauties be the happy cause/of Hamlet’s wildness”

At the time when the marriage between Anne and Sidney was arranged the Earl of Oxford was, socially, “out of Anne’s star.” Now Cecil’s care for the social and material advancement of his own family is one of the outstanding features of his policy. From this point of view the marriage of his daughter to one of the foremost of the ancient nobility, and a man of vast possessions, would be a great acquisition and the gratification of a high personal ambition. These social connections evidently meant much to him, for he had tried to make out an aristocratic ancestry for himself and had failed. Whether or not Elizabeth would sanction such an alliance might, however, be considered extremely doubtful; and if she were to consent, such consent would be almost as great a concession to Cecil as was that of Denmark’s King and Queen to the marriage of Hamlet with the daughter of Polonius. [p. 257]

10) Act III. i. 90-150: “Where’s your father?”

The cryptic explanation of his conduct which we have just quoted seems to have been the only one which Oxford would vouchsafe – to Burleigh at any rate. Burleigh complains of Oxford’s taciturnity in the matter: that he would only reply, “I have answered you” — which is strikingly suggestive of Shylock’s laconic expression “Are you answered?” One account suggests that the attitude he assumed on his arrival was a sudden and erratic change. If this be correct it is certainly suggestive of that lightning-like change one notices in Hamlet’s bearing towards, Ophelia, when he detects that she is allowing herself to be made the tool of her father in spying upon Hamlet himself (Act III, scene 1 ). [p. 277]

[later in Shakespeare Identified]: …Lady Oxford’s fault was probably no worse than that of having weakly succumbed to, a masterful father, or rather two masterful parents. Ophelia’s weakness, then, in permitting herself to be made her father’s tool in intruding upon Hamlet, certainly suggests her as a possible dramatic analogue to the unfortunate Lady Oxford. [p. 283]

11) Act III. ii. 91-2: “My lord, you play’d once/ i’ th’ university, you say?

It is claimed by some writers that Shakespeare shows a knowledge of the universities. Such contact as Edward de Vere had with them would be sufficient to account for that knowledge, whilst the apparently small part it played in his life would quite agree with the almost negligible part that college and university matters occupy in the plays. There are only two occasions on which Shakespeare mentions the word “university.” Hamlet, in poking fun at Polonius, draws him out by exciting his vanity about what he had done “at the university.” [p. 244]

12) Act III. iv. 24: “I took thee for thy better”

Oxford had inflicted a wound on an under-cook in Burleigh’s employ, and this wound unfortunately proved fatal. None of the circumstances are told, possibly because they are unknown, but, like everything else, the event must needs be set down to Oxford’s discredit. Now, remembering Burleigh’s spying methods and the peculiar circumstances under which Polonius received his death wound at the hands of Hamlet, we may possibly find in the drama a suggestion of something that had actually happened in the experience of its author; especially in view of Hamlet’s exclamation:

“Thou wretched, rash, intruding fool, farewell!

I took thee for thy better.” [p. 262]

13) Act V. i.: 60-4: “In youth, when I did love”

Now, by a curious chance, the last poem in the “Vaux” collection, the poem therefore that immediately precedes the De Vere collection, is the identical song of Lord Vaux which “Shakespeare” adapts for the use of the gravedigger in “Hamlet.” This may not have much weight as evidence. Nevertheless, if it can be maintained, as it reasonably may, that Edward de Vere in his earliest poetic efforts built upon foundations that Lord Vaux had laid, then the reappearance of an old song of Lord Vaux, in Shakespeare’s supreme masterpiece, forty years after the death of the writer of the song, is certainly not without significance as part of our general argument. [p. 170]

14) Act V. i. 75-7: “…the pate of a politician, one that would circumvent God”

Oxford’s general relationship to those politicians, moreover, is most clearly reflected in the works of Shakespeare where the very word “politician” is a term of derision and contempt.

“That skull had a tongue in it and could sing once; how the knave jowls it to the ground as if it were Cain’s jaw-bone that did the first murder! It might be the pate of a politician, one that would circumvent God, might it not?” [p. 357]

15) Act V. ii. 1-81: “Up from my cabin, my sea-gown scarfed about me”

Hamlet’s sea experiences we observe stand in direct association with the death of Ophelia. It is whilst he is away that she dies. He returns at the time of her burial, and after the graveyard scene resumes with Horatio the discussion of his sea adventures. As, then, the attitude of Hamlet to Ophelia resembles in some particular that of Oxford to his wife, we may hope, at any rate, that, as “Shakespeare,” he gives us in the famous graveyard scene a revelation of the true state of his affections: a supposition which even his conduct at the time of their rupture quite justifies.

The death of Lady Oxford, and the subsidence of the national excitement in relation to the Spanish Armada, following, as they do, closely upon the last indications we have of his theatrical enterprises, may be taken as marking the time at which he began “to sit in idle cell,” or the beginning of the third period of his life. [p. 362]

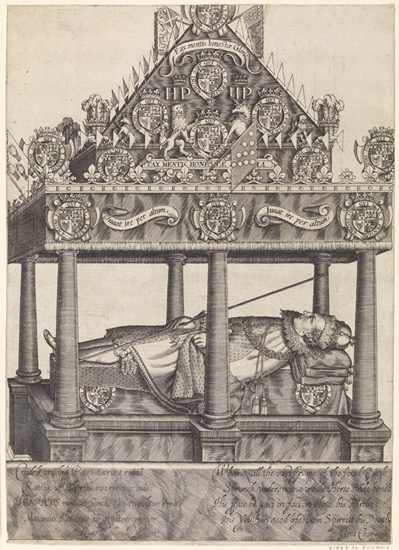

16) Act V. ii. 291-3; 299-302: “Now cracks a noble heart”

“Horatio, I am dead;

Thou livest; report me and my cause aright

To the unsatisfied.

* * *

If ever thou didst hold me in. thy heart

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain

To tell my story.”

Hamlet (V. 2).

“An unlifted shadow somehow lies across his memory.”

Dr. Grosart. [pg. 209]

!["Come, thou tortoise! when? [Re-enter ARIEL like a water-nymph] Fine apparition! My quaint Ariel..." ThouTortoise](http://www.edwardoxenford.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ThouTortoise.jpg)

Recent Comments