Did Ben Jonson write The Tempest’s masque?

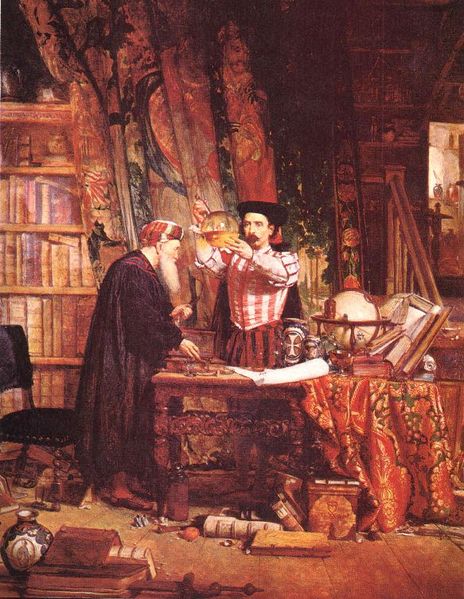

In his essay “Another Jonson Critic” (The Ben Jonson Journal 18.1, 2011) Andrew Gurr observes: “Shakespeare never wrote any masques for the Court. So why did he create part of one for The Tempest?” His question serves as launchpad for a searching review of the many similarities and echoes that scholars have long noted between Ben Jonson’s pre-1610 masques and the one we find in The Tempest. Aided by speculations as to the “consistently lively and intimate relationship” between these two famous rivals, Gurr concludes that Shakespeare’s apparent awareness of Jonson’s masques, and Prospero’s abrupt dismissal of the pageantry when he recalls Caliban’s conspiracy, works as a “quiet comment on the pretensions inherent in Jonson’s courtly masquing.”

But is this an adequate explanation for the uncanny accuracy of Shakespeare’s imitation? Jonson, after all, knew these transient pretensions firsthand, and Prospero’s “Our revels now are ended” speech directly echoes sentiments he’d already expressed in Hymenaei, published in 1606. With so many examples of his influence over the form and content of this masque, why, I wonder, did Andrew Gurr not ask if Jonson might have written it? Given the recent scholarship on “collaboration” in Shakespeare’s canon, especially among the later plays, further investigation into Ben Jonson’s hand within The Tempest certainly seems justified.

What follows are just a few of the similarities to Jonson’s masques, as well as Jonson’s thinking about the phenomena of the court masque, as noted by Gurr:

* Transcience: In his preface to Hymenaei, Jonson “wrote of the division between a masque’s “soule,” it’s poetry, and the materiality and transience of its staging. The soul, he argued, had the “lasting” impact. Otherwise, “all the glorie of all these solemnities had perish’d like a blaze, and gone out in the beholders eyes.” Though Gurr hesitates to say so, Jonson’s skepticism about “shows” in his preface actually mirrors Prospero’s dismissal in his “Our revels now are ended” speech, where, just as swiftly as he can clap his hand, the “insubstantial pageant” he’s orchestrated will fade and dissolve, like a blazing moment of sunset.

Instead of acknowledging that Jonson and Shakespeare have the same views on this transcience of the Jacobean court spectacles, Gurr attempts to find difference where there is none: “Jonson’s introductory notes to his 1610 masque must have stimulated Shakespeare’s thinking about such shows. Whatever his reason for so abruptly truncating The Tempest’s masque, Shakespeare seems to have developed his own view of the new art. His feelings seem to have been altogether more modest, or at least more modulated.”

* The Great Globe: Universally and inextricably linked in the public mind of today to William Shakespeare and his Globe theatre, this may not have been the case in early Jacobean London, as Gurr’s next observation suggests:

Hymenaei has several features that must have registered in Shakespeare’s mind… Not the least of the apparent echoes of [Jonson’s] masque in The Tempest is the great orb of silver and gilt, the giant “microcosme, or Globe, (figuring Man)” designed by Inigo Jones. …Whether or not Prospero alludes to it directly when he specifies “the great Globe it selfe” while declaring that “Our Revels now are ended,” a few people in the audience at the Blackfriars, not least Jonson himself, might have been expected to see the link.

To further illustrate, Gurr quotes from John Pory’s letter to Sir Robert Cotton dated 7 January, 1606:

Ben Jonson turned the globe of the earth standing behind the altar, and within the Concave sate the 8 men-maskers representing the 4 humours and the fower affections who leapt forth to disturb the sacrifice to union…

Don’t you just love the image of Ben Jonson turning that huge mechanical globe, with all those gorgeously costumed courtiers sweating in its concave belly? Note also how his eight men-masquers leapt forth to disturb. This mirrors the reason for Prospero’s abrupt ending of the masque: the memory of Caliban and his co-conspirators leapt forth to disturb him, the deposed duke of Milan and self-appointed guardian of the island’s “commonwealth”.

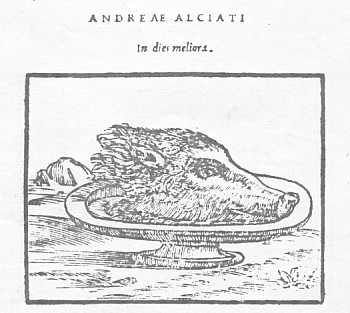

* Reason: Jonson’s affection for the quality of “wakeful reason” is well-documented in his early Epode, included in Chester’s Love’s Martyr. Without reaching so far back, Gurr easily connects Prospero’s reliance on reason with Jonson’s symbolic portrayal of the virtue:

Moreover, that in Jonson’s Hymenaei it should be Reason who was the one to restore order, sitting on top of Hymenaei’s globe and descending from it to quell the disruptive Humours and Affections, such a show of control seems nicely echoed in Prospero’s own subsequent dismissal of his disordered masquers.”

Jonson and Shakespeare do seem to be thinking along similar lines at this time, as when we find Prospero declaring, “Yet with my nobler reason gains’t my fury…” And Jonson’s early use of “wakeful Reason” calls to mind the sleepy terms that Prospero uses to dismiss the pageant when his spy, Ariel, reminds him of the “foul conspiracy”:

We are such stuff/as dreams are made on…

…our little life is rounded by a sleep…

…My brain is troubled, be not disturbed with my infirmity

Had Prospero and his “nobler reason” been awake, rather than invested in staging this dreamy “vanity” (which for some reason he seems to think is expected of him), would he have forgotten Caliban’s mischief?

* Drawn swords: The anti-masque is a Jonsonian innovation, written to portray the disorder that the order of a masque will reform, through its symbolic poetry and pageantry. At this point in his essay, Gurr moves beyond the Tempest’s masque to a consideration of where, if at all, we may find the play’s “anti-masque”. He cites Catherine M. Shaw: “who identifies the play’s antimasque as Ariel’s previous maddening of Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio at the end of act 3 while Prospero is standing to view it ‘on the top’.” If we follow Shaw’s line of thinking as regards the anti-masque, we find it leads us to another echo of Jonson’s Hymenaei:

…Alonso and Antonio have both rebelled against Reason by ‘violating the unity of family and state,’ making them draw their swords just as the masquers do in Hymenaei.

* “on the top”: As we’ve just seen, this phrase appears in act 3, scene 3, where Shaw locates the anti-masque of the play. Gurr draws our attention to a similar phrase in Jonson’s Hymenaei, where

“a statue of Jupiter is present above the pair, positioned ‘standing in the toppe (figuring the heaven) brandishing his thunder.’ This may well have been reflected in Cymbeline’s Jupiter, suspended from the Globe’s heavens… as much as in Prospero, positioned to watch the banquet during Ariel’s appearance as the Harpy in a superior position specified by the stage direction only as “on the top,” a distinctive location not repeated anywhere in any other play.”

This echo of a unique stage direction in two of Shakespeare’s later plays seems to position Jonson as the Jacobean trend-setter in his staging effects. Having exceeded my 1,000 word limit for a blog post, I’ll save the remainder of Gurr’s very useful essay for another day. Thank you for visiting the EO Review.

!["Come, thou tortoise! when? [Re-enter ARIEL like a water-nymph] Fine apparition! My quaint Ariel..." ThouTortoise](http://www.edwardoxenford.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ThouTortoise.jpg)

Recent Comments