One Phoenix?

“Sebastian’s pointed allusion to “one tree [in Arabia], the Phoenix throne; one Phoenix at this hour reigning there” (3.3.21-24) can now be appreciated – as it would be in any play dated before 1604 – as a topical compliment to an elderly Queen known as the Phoenix, Elizabeth I (1533- 1603).” Stritmatter & Kositsky, On the Date, Sources and Design of Shakespeare’s Tempest, McFarland, 2013

In my last post, Phoenix of the Tempest, we saw how Sebastian’s allusion, followed by references to the traveler Puntarvolo of Jonson’s Every Man Out of His Humour, could, indeed, direct us to a time during Elizabeth’s reign. Specifically, in a play attributed to Shakespeare, I believe we’re invited to revisit the “Poetical Essaies” on the topic of the Phoenix that he and Ben Jonson contributed to Robert Chester’s Love’s Martyr. Could it be that the author is also inviting us to hear a compliment to Elizabeth while she still reigned, as Stritmatter and Kositsky imagine?

Not necessarily so. Allusions are notoriously subjective, even more so when so much is at stake, as it is for those who hold that Oxford (who died on June 24, 1604) wrote “Shakespeare” and “Shakespeare” wrote The Tempest. We must be on guard against hidden assumptions that may limit the scope of our inquiry. For example, as evidence that Sebastian’s Phoenix refers to Elizabeth, Stritmatter and Kositsky state, (in a footnote to the book’s first reference to the Phoenix, ch. 7, p. 79, fn. 36):

Incidentally, the passage suggests that Queen Elizabeth was alive when the play was written: her association with the Phoenix is too well known to require detailed exposition. As early as 1574 medallions were struck bearing her image on one side and the phoenix on the other, and in 1575 she sat for the “phoenix portrait” by Nicholas Hilliard wearing one. [A second footnote, to ch. 9, repeats this assertion almost verbatim.]

Notice how “too well known” lullabies us into complacency. Of course, Elizabeth adopted and nurtured the Phoenix myth for herself, but she wasn’t the only Phoenix of the times. In 1593, The Phoenix Nest included poems of grief honoring the slain Philip Sidney as a Phoenix (with “E.O” as one of the contributors; his poem was later reprinted in England’s Helicon as by the “Earle of Oxenford“). By marrying Sidney’s widow, Essex symbolically rose from Philip’s ashes to carry on the Sidnean flame of virtue. After the beheading of Essex in 1601, his role as Sidney’s successor for the mantle of true, virtuous phoenix (or lover of the phoenix) may have been on the minds of the poets – Shakespeare included – who contributed to Love’s Martyr.

Although they abstain from offering a likely date by which the earl of Oxenford would have written The Tempest, “any play dated before 1604” is the time frame that Stritmatter and Kositsky stake out for Sebastian’s supposed compliment to Elizabeth as a living Phoenix. Perhaps they meant to say “any play dated before Elizabeth’s death in March of 1603”? Once she was gone, the mantle of Phoenix quickly passed, with imperial emphasis, to James:

The most common image with which James was associated, especially in the immediate aftermath of his succession, was that of the phoenix. A device with which writers had lauded Queen Elizabeth, it was one which could be used to celebrate the new king even as it remembered his predecessor. A long-time imperial motif, its use dated back to the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine… As James had returned to the throne of Britain as a Constantine so too was he like Britain reborn. Theatre and Empire: Great Britain on the London Stages under James VI and I by Tristan Marshall

The list of examples Marshall provides should quickly alert us to the dangers of using Sebastian’s cry of belief in a Phoenix as either a reference to Elizabeth or as a dating marker for The Tempest:

In praising James, use of the phoenix began during the period of mourning for the queen. ‘One Phenix dead, another doth suruiue‘ and ‘thus is a phoenix of her ashes bred‘ wrote the Cambridge contributors to Sorrows Ioy (1603), while Henry Campion described ‘that Phoenix rare, whom all were loath to leaue’. Sylvester’s translation of Du Bartas’s Divine Weeks and Works (1608) mused: ‘from spicie Ashes to the sacred URNE of our dead Phoenix (dear ELIZABETH), A new true PHOENIX lively flourisheth… JAMES, thou just Heire’. Welcoming James to his capital on behalf of its sheriffs the MP and wit Richard Martin effused how ‘out of the ashes of this Phoenix wert thou, King James, borne for our good, the bright starre of the North’. Henry Petowe’s 1603 poem reporting James’s coronation, England’s Caesar, claimed that the king was ‘the Phoenix of all Soueraignty‘ while Dekker’s arch for Jame’s welcome to London, Nova Arabia Felix, associated Britain with ‘happy Arabia…’ …The king’s arrival before the arch represented the phoenix arising out of the ashes of the dead queen…

These references to James as a phoenix highlight another problem with using the soft evidence of topical allusions to date the composition of an entire play: changes or additions may have been made at any time before publication, especially to a script revived soon after greatly altered circumstances. Regardless of who we believe wrote Shakespeare, we should never lose sight of the documentary evidence we do have for dating this play: the first recorded performance at court of 1611, followed by a second royal production in 1613, along with the 1623 date of first publication in the First Folio.

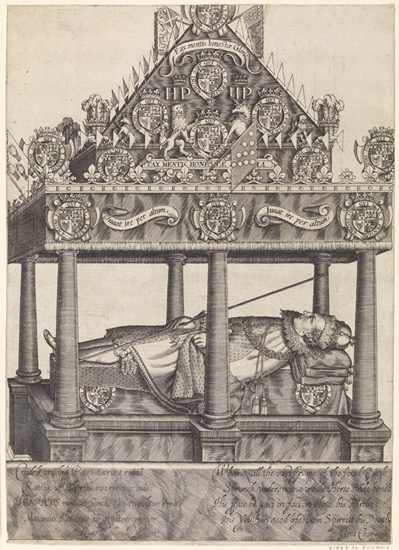

By the time the court saw The Tempest for a second time in 1613, they’d just mourned the death of Prince Henry in 1612 and were in the midst of celebrating the wedding of his sister Elizabeth to Frederick, Elector Palatine, on Feb 14, 1613. Tristan Marshall documents another flurry of Phoenix references inspired by these momentous changes:

Use of the phoenix image was to be given new impetus when James’s heir apparent died prematurely in 1612. The death of Prince Henry was lamented by Christopher Brooke – ‘…this Phoenix …haue sacrificed his life in funerall flame‘ – while Protestant hopes were transferred to his sister and her husband, of which couple Robert Allyne wrote:

As Phoenix burnes herselfe against the Sunne,

That from her dust may spring another one…

So now, raise up a world of royall seed.

That may adorne the earth when ye are dead.

It is no coincidence that Phineas Pett built and launched a ship named the Phoenix in honour of the Princess Elizabeth before her departure with her husband, while Donne refers to the couple repeatedly as being two Phoenixes in his Epithalamion for their marriage.

As should now be evident, in a play first established as a stable text in 1623, Sebastian’s reference to a Phoenix still reigning could apply to Elizabeth as Anne Boleyn’s heir, to Essex as Philip Sidney’s heir, to James as Queen Elizabeth’s heir (1603-5), to the Stuart Princess Elizabeth as her brother Henry’s heir (1612-13), or to none of the above. I believe the context best fits Jonson’s idealized Phoenix: a being infused with all Virtue and no Vice, wherein Passsion submits to Reason, and Love embraces Chastity. As I hope to show in future posts, this was Prospero’s vision as well. On Jonson’s terms, Ariel’s magic begins the work of transforming the treasonous fool Sebastian from a monster into a man.

~Marie Merkel

Recent Comments