J. T. Looney part 2: “Self-Revelation in Hamlet”?

Sorry, no pirates this time. However, in his chapter devoted to Hamlet, Looney expands on his earlier observations with 18 additional parallels, correspondences or topical allusions between Oxford’s life and Shakespeare’s play. For ease of reference, I’ve collated these new items (in boldface) with the sixteen parallels tallied in my blog entry of May 9, 2015 (J. T. Looney on Hamlet, Part 1).

Once again, I’ve arranged Looney’s suggested parallels according to their approximate appearance within the play as it unfolds. The excerpts provided below are much briefer than those I posted last time, with links to Shakespeare Identified when available through Google books. Not included are observations from Looney of so general a nature that they defied quick synopsis, much less a direct link to any particular moment in the play or to a supporting historical document.

What follows is merely a list, with no endorsement intended. The question marks following each item invite skepticism and debate, as the next logical step after these have been noted and reviewed. I’ve even resisted the temptation to separate those I feel are stronger from items that I would set aside as poorly grounded.

If you are new to these pages, please see “Hamlet’s Parallel Universe” for background on this particular project. For those who’ve been following, either here or on Facebook, a quick reminder of what’s at stake and how I’ll approach the problem:

Must the establishment of true believers – and by believers I mean those who accept William of Stratford as Shakespeare as well as those who choose Oxford – ignore the evidence of parallels and/or allusions in the text of Hamlet to Essex or Rutland, King James, Derby or Sidney, to protect their candidate? Absent the pressure of authorship contentions, earlier scholars allowed a much wider lens to the author’s hawking eye.

That’s the way I propose to look at Tom Reedy’s four candidates (plus Sidney) for “closer and more abundant” parallels with Hamlet: as if there were no Shakespeare Authorship Question. Shakespeare will simply be Shakespeare, sans quotes or hyphens. For the purpose of this investigation, he’s the author of the Hamlet text we find published in three separate editions: 1603, 1604 and 1623.

Looney’s major and minor suggestions of correspondence between Hamlet and Oxford:

1) 1.1.70-78: Allusion to the Armada?

2) 1.2.138: Hamlet & Oxford both supplanted after remarriage of mother?

3) 1.2.146: Hamlet & Oxford both exhibit lack of trust in womanhood?

4) 1.2.129-58: Hamlet & Oxford both possess large mental reserves and secretiveness?

5) 1.2.58-61;112-16: Hamlet & Oxford both denied permission to travel?

6) 1.2.187: Hamlet & Oxford both exhibit father-worship?

7) 1.3.6 etc.: If Polonius is Burghley and Hamlet is Oxford, then Ophelia is Anne Cecil?

8) 1.3.18: Hamlet & Oxford both could not marry as they chose?

9) 1.3.49: Laertes mirrors Thomas Cecil?

10) 1.3.58: Polonius’ advice to son parallels Burghley’s advice to son(s)?

11) 1.3.78: Polonius mirrors Burghley on self-interest?

12) 1.5.179: Hamlet & Oxford both “put an antic disposition on”?

13) 1.5.9-13 and elsewhere: Catholic-skeptic Hamlet mirrors Catholic-atheist Oxford?

14) 2.1.1-74: Polonius & Burghley both spied on their sons?

15) 2.1.58: Polonius & Burghley both wise about tennis court quarrels?

16) 2.2.398-405: Hamlet’s jest to Polonius re: “Jephthah” fits Burghley’s sacrifice of Anne?

17) 2.2.140: Hamlet a Prince & Oxford like a prince?

18) 2.2.356 (and more): Hamlet w/players mirrors Oxford w/poets & his troupe?

19) 3.1.39-40 (and more): Social status of Polonius & Ophelia mirrors Burghley and Anne?

20) 3.1.90-150: Hamlet sees Ophelia as her father’s pawn mirrors Oxford & Anne Cecil?

21) 3.1.104: Hamlet’s use of ‘honest’ to Ophelia mirrors Burghley’s use of honest?

22) 3.2.91-2: Shakespeare’s 2 uses of “university” parallels Oxford’s slight attendance?

23) 3.2.246: Hamlet & Oxford both show interest in Italy?

24) 3.2.275; 340-3: Hamlet & Oxford both musically inclined?

25) 3.2.347-54: Hamlet & Oxford both resist attempts to know their mind?

26) 3.2.57-69: Horatio’s character matches Horace Vere’s character?

27) 3.4.25: Hamlet stabs Polonius, Oxford stabs Bricknell?

28) 4.5.160: Ophelia and Anne Cecil both sweet maids?

29) 4.6.11-20: Hamlet & Oxford both participate in sea fight?

30) 4.7.83 to end: Hamlet & Oxford both involved in swordplay & duels?

31) 5.1.60-4: Gravedigger’s song from Lord Vaux of special significance for Oxford?

32) 5.1.75-7: Hamlet & Oxford both exhibit contempt for politicians?

33) 5.1.232: Hamlet & Oxford both return from sea to the death of lover/wife?

34) 5.1.280: Hamlet’s love for Laertes mirrors Oxford’s regard for Thomas Cecil?

35) 5.2.291-3: Hamlet’s “wounded name” reflected in “unlifted shadow” o’er Oxford’s name?

36) 5.2.309: Election of Fortinbras parallels James I in 1603?

37) 5.2.349: Hamlet & Oxford both want (desire and lack) military vocation?

Relevant excerpts from Looney’s Shakespeare Identified with links to full text:

1.2.138: “But two months dead”: Hamlet & Oxford both are supplanted after remarriage of mother?

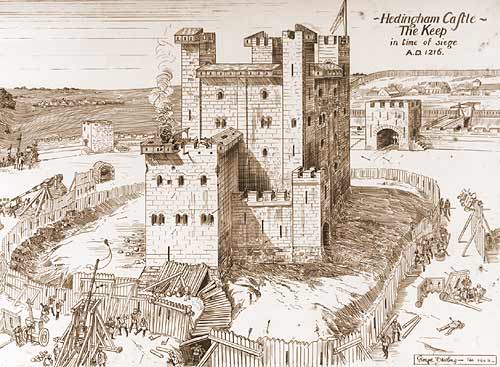

As, moreover, her death occurred at Castle Hedingham, one of the chief of the ancestral homes of the De Veres, it looks as though Oxford’s stepfather had established himself on the family estates…

1.2.146: “Frailty, thy name is woman”: Hamlet & Oxford both exhibit lack of trust in womanhood?

With a capacity for intense affection, such as we have already pointed out in “Shakespeare” and in De Vere, Hamlet was incapable of any real trust in womanhood. His faith had been shattered by the inconstancy of his own mother. This curious combination of intense affectionateness with weakness of faith in women is therefore characteristic of all three, “Shakespeare” (in his sonnets), Hamlet, and De Vere.

1.2.129-58:”O that this too too solid flesh would melt”: Hamlet & Oxford both exhibit “large mental reserves” and secretiveness

All that quickness of the senses which marks alike the work of De Vere and Shakespeare manifests itself in the person of Hamlet. He misses nothing; and everything he sees or hears opens some new avenue to the “inmost parts” of those about him. A man like this is almost foredoomed to a tragic loneliness…

1.3.6 etc.: “the trifling of his favour”: If Polonius is Burghley, and Hamlet is Oxford, then Ophelia is Anne Cecil?

For, although Polonius’s daughter, Ophelia, was not actually Hamlet’s wife, she represents that relationship in the play…

1.3.49: “Like a puffed and reckless libertine”: Laertes mirrors Thomas Cecil?

The tendency towards irregularities, at which Ophelia hints in her parting words to her brother, is strongly suggestive of Thomas Cecil’s life in Paris… …We are told that Thomas Cecil incurred his father’s displeasure by his “slothfulness,” “extravagance,” “carelessness in dress,” “inordinate love of unmeet plays, as dice and cards”; and that he learnt to dance and play at tennis.

1.3.58: “And these few precepts in thy memory”: Polonius’ advice to son parallels Burghley’s advice to son?

Probably the most conclusive evidence that Polonius is Burleigh is to be found in the best-known lines which Shakespeare has put into the mouth of Denmark’s minister — the string of worldly-wise maxims which he bestows upon his son Laertes (Act 1. 3)…

1.3.78: “To thine own self be true”: Polonius mirrors Burghley on self-interest?

This is quite in keeping with the cynical egoism of Burleigh’s advice, “Beware of being surety for thy best friends”; but “keep some great man for thy friend.”…

1.5.9-13 and elsewhere: “Doomed for a certain turn”: Catholic-skeptic Hamlet mirrors Catholic-atheist Oxford?

…All this, too, is in accord with the shadowy indications that are given of Oxford’s dealings with religion: his profession of Catholicism at one time, the accusation of atheism against him at another.

1.5.179: Hamlet & EO both “put an antic disposition on”?

…It is a match of wits in which the ablest mind wins by allowing his inferior antagonists to suppose him mentally deficient. Now the records we have of Oxford represent his eccentricity in his early and middle period as being of an extreme character, and if we suppose him to be Shakespeare, we can quite believe that his own secret purposes were being pursued partly under a mask of vagary.

2.2.140: “Lord Hamlet is a Prince, out of thy star”: Hamlet a Prince & Oxford like a prince?

Oxford, of course, was not a prince of royal blood: but then there were no princes of royal blood at the English court, and the Earl of Oxford, in his younger days, was the nearest approach to a royal prince that the English court could boast. In the matter of ancient lineage and territorial establishment a descendant of Aubrey de Vere had nothing to fear in comparison with a descendant of Owen Tudor…

3.1.103: “Ha, ha? Are you honest?”: Hamlet’s use of ‘honest’ to Ophelia mirrors Burghley’s use of honest?

Hamlet’s use of the double sense of the word “honest” in a question to Ophelia — the identical word which in its worse sense was, thrust to the front by Burleigh respecting the rupture between Lord and Lady Oxford…

3.2.57-69: “blest are those/ whose blood and judgement are so well commingled”: Horatio’s character matches Horace Vere’s character?

The passage in which Hamlet describes the character of Horatio ought therefore to be compared with what Fuller says of Horatio de Vere.

3.2.246: “The story is extent, and writ in choice Italian”: Hamlet & Oxford both show interest in Italy?

In the same scene he shows his interest in Italy.

3.2.275; 340-3: “Come, some music. Come, the recorders”: Hamlet & Oxford both musically inclined?

Hamlet expresses his musical feeling and even suggests musical skill in the “recorder” scene.

3.2.347-54: “You would play upon me”:Hamlet & Oxford both resist attempts to know their mind?

Now this resistance to interference stands out clearly at the time when Oxford, having returned from abroad, is reported to have behaved in a strange manner towards Lady Oxford…

4.6.11-20:”Ere we were two days old at sea…”: Hamlet & Oxford both participate in sea-fight?

…and his actual participation in a sea-fight is duly recorded.

4.5.103: “Laertes shall be king” parallels Essex and his Rebellion?

Not as an important part of our argument, but as strengthening the feeling of a connection between the play of Hamlet and events in England at the time when it appeared, the rising of the citizens of Elsinor with the cry “Laertes shall be king,” is suggestive of the rising in London under Essex…

4.5.160: “Dear maid, kind sister, Sweet Ophelia”: Ophelia and Anne Cecil both sweet maids?

We notice, however, that the few words the Queen speaks respecting Ophelia harp on the idea of that sweetness which, we have noticed, Lady Oxford…

4.7.83 to end: Hamlet & Oxford both involved in swordplay & duels?

The duelling in which he takes part also has its counterpart in the life of Oxford…

5.1.280: “I lov’d you ever”:Hamlet’s love for Laertes matches Oxford’s for Thomas Cecil?

Now the fact is that Thomas Cecil was one entirely out of touch with and in many ways quite antagonistic to Burleigh and his policy… …He was also one of those who, along with Oxford, favoured the Queen’s, marriage with the Duke of Alençon, in direct opposition to the policy of Burleigh…

5.2.309:”He has my dying voice”: election of Fortinbras mirrors James I in 1603?

Again the change, not only in the occupants of the throne but also of dynasties in Denmark, “the election lighting on Fortinbras,” from the neighbouring country of Poland, is suggestive of a similar change in England when, consequent upon the royal nomination, England received the first of a new dynasty from the neighbouring country of Scotland. In this case Fortinbras would be James I, and Oxford’s officiating at the coronation might appear as an equivalent to Hamlet’s dying vote, “He has my dying voice.”

5.2.349: “Bear Hamlet like a soldier”: Hamlet & Oxford both want (desire and lack) military vocation?

His unrealized ambitions for a military vocation are indicated in the final scene…

Is this all of them? If you think I’ve missed something, please let me know!

Recent Comments